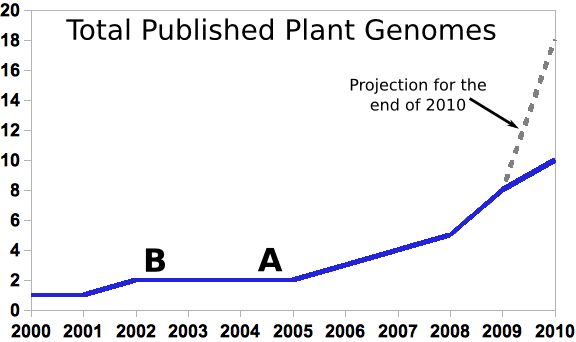

One of the themes, looking over the abstracts and talks for this year’s maize meeting before I leave is that a year from now we can expect to have much more detailed information about where genes are expressed in corn, and at what levels. One of the great dividends of the dropping cost and increasing speed of short read sequencing.

At this meeting alone we’ll be hearing about the incredibly detailed leaf transcriptome[1] (which seperates out expression of four developmental zones of the leaf, plus uses laser capture to look at the expression of genes the bundle sheath and mesophyll cells within the maize leaf seperately). And at least two posters on the subject also caught my eye (although there may be a lot more that involve profiling expression using high throughput sequencing). Two groups based at Oregon State and Stanford are in the process of sequencing the transcriptomes of the male and female gametophytes* of maize[2], and a group based primarily at Cold Spring Harbor is in the proccess of sequencing the transcriptome of developing ears (the kind covered in corn kernels, not the kind you hear out of)[3]. Both of these transcriptomes actually represents a number of seperate data sets from different tissue types and/or developmental stages.

All these datasets makes me wish the Fort Lauderdale Accords** applied to expression data in addition to genome sequences themselves, but since it doesn’t, I’ll happily oooh and awww over other people’s cool data.

A special thanks to Andrea Eveland’s abstract for introducing me to units that can actually quantify the wa expression is measured in these studies RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase of exon per Million reads).

*Plants practice alteration of generations, switching between diploid (two copies of the genome, one from each parent) and haploid (only a single copies of their genome) multicellular forms of life. In flowering plants, the kind we spend most of our time with, the haploid generation is almost vestigial, but it still exists. Plant pollen contains an entire male haploid plant (the male gametophyte), which has been reduced to a mere three cells (two which are sperm cells). The female gametophytes of flowering plants are only a little larger, at seven cells. In other plants, the gametophyte can exist as a free living life form visible to the naked eye.

**The agreement that allows genome sequence data to be released to the whole community before the people who sequenced that genome have published their paper.

[1] Pinghua Li et al. “Characterization of the maize leaf transcriptome through ultra high-throughput sequencing” Talk #14 2010 Maize Meeting (Presented by Thomas Brutnell)

[2] Rex A. Cole et al. “Analysis of the Maize Gametophytic Transcriptomes” Poster #27 2010 Maize Meeting (Presented by Matt Evans)

[3] Andrea L. Eveland et al. “Transcriptome sequencing and expression profiling during maize inflorescence development.” Poster #113 2010 Maize Meeting