If you are an undergraduate at UC-Berkeley interested in gaining research experience or know someone who is, check out our lab entry at the Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP). The project description is a huge mouthful, and personally I think it sounds much more intimidating than it needs to be. So below is my argument why, if you’re interested in a research career or graduate school, you should consider in working in my lab, even if you aren’t specifically interested in genome evolution or computational biology. (more…)

November 30, 2010

November 28, 2010

Crops of the Americas

But the Native Americans weren’t without any useful proto-domesticated plants. Tobacco and chocolate are two that come to mind.

Wait…. what? Take a minute and think about that statement. When you think about crops that were a lot more than proto-domesticated long before europeans made it over to the western hemisphere, what should be the first thing that comes to mind?

…

…

It’s in the URL of my website! Corn. (more…)

November 27, 2010

Hybrid vigor and missing genes

Thinking about defining the number of genes present in the maize genome reminded me of an old* story about the trouble of defining what truly represents a gene and how really awesome ideas can sometimes come years before the data needed to support them.

The year is 2002. The first complete version of the human genome is still a year away. The genomes of two plant species have already been published (rice and arabidopsis) but in terms of shere genome size, both species are a drop in the bucket compared to the human genome, or other plant genomes like corn or wheat. But none of this is particularly important except to set the stage.

Two researchers at Rutgers University were sequencing a tiny piece of the maize genome (~0.01%) that surrounded a single gene call bronze1 — the fifth most studied gene in maize — when they found something unexpected.

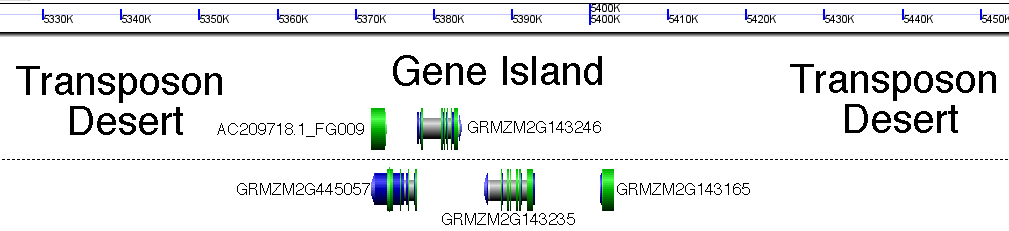

They had previously 10 identified genes in a single stretch of 32-kb of the maize genome. (A similar gene density throughout the remainder of the maize genome would have resulted in a maize genome containing more than 700,000 genes!) However it was already known that the maize genome was split between small gene-rich islands and vast desolate expanses of transposons (referred to as transposon nests**), and in fact the same study identified a couple of these nests of transposons on either side of their gene rich island (see part A of the second picture in this post).

Below I'll use cartoons, but here's a real and to scale example of a gene rich island I picked at random from maize chromosome 3. Genes and intergenic spaces are to scale. Base image generated with GenomeViewer, part of the CoGe toolkit. http://www.genomevolution.org/CoGe/

Their initial sequencing used DNA from a breed of corn called McC, which I must admit I’ve only ever read about in this particular paper. However, when they decided to sequenced the same region from the genome of B73*** they made three discoveries which I’ve listed in increasing order of strangeness: (more…)

November 23, 2010

New maize gene models are out!

These are the official annotations for version two of the maize genome assembly. For the official release I need to point you to a text file on an FTP site (sorry). You can download all the new genomic information here.

In version one the maize sequencing consortium released two separate sets of gene models. A list of 32,400 high confidence gene models known as the maize “filtered gene set”, and a list of over 110,000 gene models known as the maize “working gene set.” There were very good reasons to do this at the time, but it was a pain for a lot of people since depending on what questions you studied you might use one set of annotations or the other.

In version two the maize genome folks have released a single set of 110,028 genes. Intimidated? So was I. Fortunately it’s not quite as intimidating a pile of data as it sounds. (more…)

November 9, 2010

Columbine and Foxtail Millet

The latest version of phytozome (v6) just came out and it includes two genomes people in my lab have been waiting on for a LONG time.

The first is Aquilegia coerulea or Blue Rock Columbine. From a comparative genomics standpoint columbine is important because its a representative of a lineage of eudicots that split off from the two biggest families in that group (the asterid and rosids), very early on. It’s also only the second plant species to be sequenced that’s known for its flowers (the first was Monkey Flower or Mimulus). Most of the ~300 megabase genome is contained within 156 large scaffolds. So not as big as whole chromosomes, but hopefully large enough for some useful syntenic analysis. The sequenced cultivar of Columbine is “Goldsmith.” You can read more details and download the genomic data here.

The second new genome is even more exciting as far as I’m concerned, but that’s because I’m a grass guy. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) is an important crop in its own right and comes from a tribe of grasses called the Paniceae that was previously unrepresented by any sequenced genome. The Paniceae are relatives of the Andropogoneae, the tribe that contains both maize/corn and sorghum (as well as cool unsequenced species like sugarcane) and the addition of Setaria will do a lot to help balance out grass phylogenetic comparisons.* A second species of Setaria (Setaria viridis) is also being sequenced (likely using this species as a road map to assemble the genome) which is being pushed by one of my old bosses as a good genetic model to study the C4 photosynthesis that makes species in both the Paniceae and Andropogoneae so much more efficient at photosynthesis than species that still do plain old vanilla** C3 photosynthesis. Almost all of the Setaria genome is contained within 24 large scaffolds, which should definitely be big enough for the syntenic analysis my lab likes to do. More details and download links here.

Both genomes are still Fort Lauderdaled, but that only means you can’t PUBLISH on them yet, can’t stop you from looking for cool stuff. That’s what I plan to do myself after lab meeting this morning. Putting this data up on the website also means the clock has started ticking on that restriction. The version of the Fort Lauderdale accord that JGI uses gives the researchers involved in sequencing the genome 12 months to get their paper published. If they don’t manage to do that, the genome becomes fair game for anyone. Which is very useful for people like me planning future research projects. One way or another, I know that by November of 2011 I will be able to publish papers that use insight gained from the Setaria and/or Columbine genomes.***

Normally I’d dig up some pictures and interesting trivia about these species, but it 4:40 in the morning out here on the west coast, so I’m going to wrap this post up and wish you folks on the east coast good morning.

*I hope to explain what I mean by this in a followup post, but I’ve learned to be careful about promising ANY updates in advance.

**I don’t know what kind of photosynthesis vanilla plants carry out.

***I’m sure both groups will beat the deadline for getting their genomes out the door, but I can think of at least one example of a research group sitting on a completely genome indefinitely which is why having early data release and expiration dates on exclusivity is so important.

November 5, 2010

Who Goes to P.A.G.?

The plant and animal genome conference is held every January in San Diego California. This will be my first year attending and I wanted to get a sense of where the researchers I’ll be listening to and mingling with are coming from.

- The USDA (145 attendees)

- Iowa State University (45 attendees)

- *Cornell University (37 attendees)

- (3) *University of California – Davis (37 attendees)

- University of Minnesota (25 attendees)

- *University of Georgia (22 attendees)

- (6) *Washington State University (22 attendees)

- University of Illinois (21 attendees)

- University of Florida (19 attendees)

- Texas A&M (17 attendees)

- *North Carolina State University (15 attendees)

- (11) *North Dakota State University (15 attendees)

- (11) *Pennsylvania State University (15 attendees)

- 14th is also a three-way tie between Clemson, Kansas and Oregon State (all with 14 attendees)

All attendee numbers are based on hastily written regular expressions and people can find a whole bunch of different ways to write the name of the same university, so these numbers should be take, at best, as minimum estimates.

Huazhong Agricultural University deserves some special recognition as the highest ranked organization based outside of the US, sending at least 13 researchers to PAG.

Last spring I did a similar calculation for this year’s maize genetics conference. Three institutions overlap between the two lists: Iowa State (ranked #5 at the maize meetings), Cornell (ranked #1), and the University of Florida (ranked #7)