In yesterday’s Transposon Week post, I discussed how transposons can spread through a species by without providing any benefit to the animals, plants, fungus, or micro-organisms that host them.

Adding a little extra useless DNA doesn’t help an organism survive, but it also doesn’t cause serious harm. But in yesterday’s post I completely avoided one serious question:

When new copies of a transposon get inserted across the genome, what happens to the DNA they land in? For what matter, what kind of DNA do transposons land in in the first place?

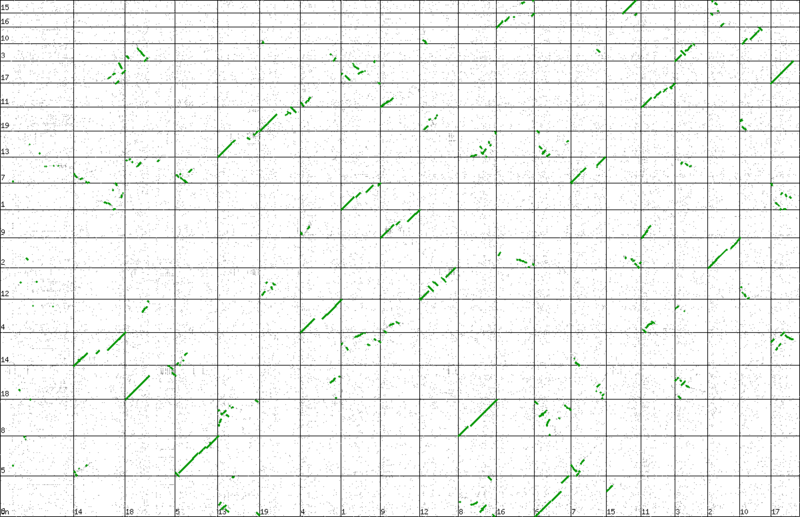

The answer to the second question is that different kinds of transposons each have their favorite places to land in the genome. Some transposons like to land in centromeres. Some transposons like to land in other transposons. Some transposons like to land near genes.

Then there are transposons like Mutator. Mutator is a maize/corn transposon that really likes to insert itself into genes. Transposons that usually land in other parts of the genome are also sometimes found in genes.

When a transposon lands in a gene, whether because that’s where it likes to insert or simply by accident, the gene stops working. Depending on which gene has to misfortune to interrupted by a transposon, the effects can range from so-subtle-we-can’t-even-detect-them to so lethal the organism dies before we get a chance to study it. In between are a whole range of effects. From severe developmental mutants, to gorgeous and apparently random streaks of color in flowers, to the spotted corn kernels which were my first introduction to the world of transposons.* (**)

Transposons are always breaking genes. The deadliest mutations disappear from the population as quickly as their appear. More subtle mutations can linger on for generations given rise to all sorts of genetic disorders. And keep in mind many genes can be broken with no visible effect at all. Anything you eat from asparagus to zuccini has the potential to contain genes broken by transposons. And depending on the gene, you’d probably never even know it.

Sorry to put this post up so late (it’s technically already Thursday) and in such a poor shape. I had some craziness in lab today and was waiting (unfortunately without any luck) to hear back about some more interesting stories I could tell about the Mutator transposon.

*To be fair, the last two are actually caused by transposons jumping OUT of genes allowing them to resume their normal function. The original mutations caused by transposons inserting into genes were to break the biochemical pathways used by Dahlia’s to make red pigment in their petals and by corn to produce purple pigment (anthocyanin) in its kernels.

**I really wish there was a good source of freely usable pictures things like transposon sectors in flowers and corn kernels. I can usually find pictures of normal plants on Flickr with creative common licenses. But I really want to be able to show you guys the cool mutants that make genetics so exciting.